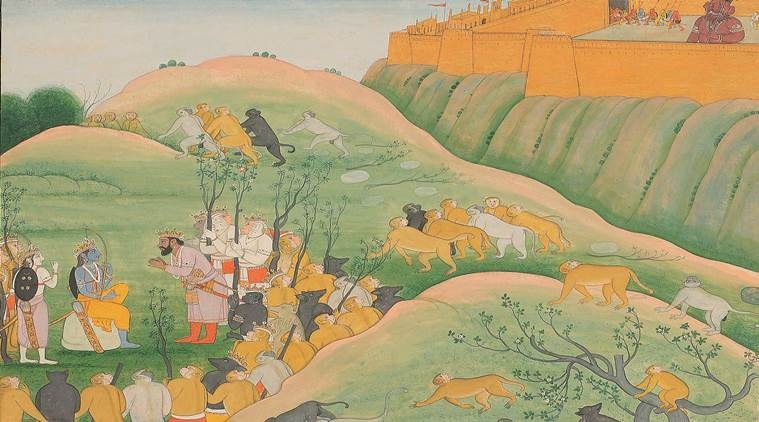

Vibhishana - Joining with Sri Rama

sense of morality or ‘anti-national’?

In the large canvas of the Ramayana, Vibhishana is a minor character. However, the rebellion of Ravana’s younger brother is a pivotal moment in the epic. For the first time, the authority of the lord of Lanka, who rose from a plebeian background to build the rakshasa empire, is challenged from within his ranks, and that too by his kin. More importantly, Vibhishana changes the terms of reference of the Rama-Ravana conflict, when he confronts Ravana on the grounds of dharma. He describes the abduction of Sita as an act of adharma and advises Ravana to free her. When Ravana rejects his advice and asks him to leave, Vibhishana crosses over to Rama’s side. Interestingly, Kumbhakarna, the other brother of Ravana, too, flags the immorality of Ravana’s abduction, but he stays put to fight for his brother, the king.

Vibhishana’s action has been debated for ages, perhaps since the time of Valmiki himself. Many have perceived it as the ultimate act of betrayal, though the poets of the Bhakti movement have held him as a stellar example of Rama bhakti. The question of dharma he flagged has since receded to the background, perhaps also influenced by his willingness to be crowned the king of Lanka, even before Ravana had been defeated. In the Valmiki Ramayana, when Vibhishana first seeks refuge with Rama, Hanuman wonders if he has left Ravana in pursuit of his throne, after learning how Rama won Kishkindha for Sugriva after killing his brother Bali. In a world where clan loyalties, kinship and blood lineages reign supreme, Vibhishana could be nothing but a traitor. However, the question of dharma that he flags continues to be relevant. Does a person stand by dharma at the cost of all else?

In the play Lankalakshmi (1974), a part of Malayalam playwright CN Sreekantan Nair’s Ramayana trilogy, Vibhishana tells Ravana that he does not “find a Lanka that has abandoned dharma and a rakshasa mob that mocks truth” a cause worth fighting for. Ravana then asks him what is the cause that drives his life. Vibhishana replies that there has to be a cause not just to live, but also to die. Ravana recalls the many battles he has waged to protect the honour of their clan, ancestors, and asks his little brother how his ideals square with these.

Vibhishana’s answer is: “A sustainable political ethic is what is necessary to protect one’s race. And, the rule of law based on dharma. My principles are the same, be it Lanka or Saketa. They don’t end at state borders. The principles I cherish are my ideals, these are my values.”

The dharmic predicament posed by Nair’s Vibhishana is one for the ages. In the modern world of nation states, the question could be rephrased: Should loyalty to the nation state override its regressions from dharma? Long ago, Vibhishana privileged dharma and his ideals over country, kin and clan. Ravana had committed adharma, and, hence, he could not be defended. Vibhishana also seems to have made a distinction between the king and the country. An act of adharma by a king is an act of betrayal of his praja (people). The king then need not be defended. And, if he needs to be replaced, so be it, even if that calls for joining hands with the king’s enemies. Rama’s intent was to defeat Ravana and regain his wife, not to subdue Lanka. If so, could Vibhishana’s joining hands with Rama against Ravana be considered treason? Or, would dharma demand that Vibhishana stand with his king and kin even if the latter’s actions revolted against his ideals?

These are concerns that resonate in public affairs even in the modern age. When Adolf Hitler seized power in Germany, Thomas Mann left his homeland and even opted to broadcast against the fascist regime from the US and Britain during World War II. There were Indians, who campaigned against the Indira Gandhi government from the West during the Emergency. And every regime insists that the praja, or citizens, stand by its regressions from the founding ideals of the republic in the name of nationalism, and abuse those who refuse to comply in the name of dharma (constitutional ideals) as anti-nationals.

Returning to Vibhishana, little is known of his afterlife post the defeat of Ravana and his ascension to the throne of Lanka. Balamaniamma, one of the greats of Malayalam poetry, visits Vibhishana and finds him restless even on the throne. The vision she unveils through him in Vibhishanan (1964) is that dharma is no less an unkind ideal as adharma is. Vibhishana is hounded by the doubt that his dead ancestors would condemn him as the destroyer of their clan. He recalls his encounter with Ravana, when he asked him: “Drop the war cry, should those with evolved intellect be playing with human lives?” Thereafter, he is reminded of Sita’s agnipravesha and wonders if dharma can be as unkind as adharma. She finds echoes of Vibhishana’s bewilderment in modern times as dharma is invoked even in use of the atom bomb, and asks if wisdom has been defeated in time’s laboratory, as the heart had lost its battle in the days of Rama!

Dharma, it is often said, is the foundational principle of Indic civilisation. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata, foundational epics of India, certainly seem to think so, and both privilege it over fealty to blood and land. Vibhishana was one of the first persons to flag this vision. His motives for doing so should not persuade us to ignore the ethical dimension in his revolt.

This article first appeared in the print edition on October 27, 2019 under the title ‘Dharma and dilemma’.

Source: indianexpress

This post is for sharing knowledge only, no intention to violate any copy rights

Source: indianexpress

This post is for sharing knowledge only, no intention to violate any copy rights

sense of morality or ‘anti-national’?

In the large canvas of the Ramayana, Vibhishana is a minor character. However, the rebellion of Ravana’s younger brother is a pivotal moment in the epic. For the first time, the authority of the lord of Lanka, who rose from a plebeian background to build the rakshasa empire, is challenged from within his ranks, and that too by his kin. More importantly, Vibhishana changes the terms of reference of the Rama-Ravana conflict, when he confronts Ravana on the grounds of dharma. He describes the abduction of Sita as an act of adharma and advises Ravana to free her. When Ravana rejects his advice and asks him to leave, Vibhishana crosses over to Rama’s side. Interestingly, Kumbhakarna, the other brother of Ravana, too, flags the immorality of Ravana’s abduction, but he stays put to fight for his brother, the king.

Vibhishana’s action has been debated for ages, perhaps since the time of Valmiki himself. Many have perceived it as the ultimate act of betrayal, though the poets of the Bhakti movement have held him as a stellar example of Rama bhakti. The question of dharma he flagged has since receded to the background, perhaps also influenced by his willingness to be crowned the king of Lanka, even before Ravana had been defeated. In the Valmiki Ramayana, when Vibhishana first seeks refuge with Rama, Hanuman wonders if he has left Ravana in pursuit of his throne, after learning how Rama won Kishkindha for Sugriva after killing his brother Bali. In a world where clan loyalties, kinship and blood lineages reign supreme, Vibhishana could be nothing but a traitor. However, the question of dharma that he flags continues to be relevant. Does a person stand by dharma at the cost of all else?

In the play Lankalakshmi (1974), a part of Malayalam playwright CN Sreekantan Nair’s Ramayana trilogy, Vibhishana tells Ravana that he does not “find a Lanka that has abandoned dharma and a rakshasa mob that mocks truth” a cause worth fighting for. Ravana then asks him what is the cause that drives his life. Vibhishana replies that there has to be a cause not just to live, but also to die. Ravana recalls the many battles he has waged to protect the honour of their clan, ancestors, and asks his little brother how his ideals square with these.

Vibhishana’s answer is: “A sustainable political ethic is what is necessary to protect one’s race. And, the rule of law based on dharma. My principles are the same, be it Lanka or Saketa. They don’t end at state borders. The principles I cherish are my ideals, these are my values.”

The dharmic predicament posed by Nair’s Vibhishana is one for the ages. In the modern world of nation states, the question could be rephrased: Should loyalty to the nation state override its regressions from dharma? Long ago, Vibhishana privileged dharma and his ideals over country, kin and clan. Ravana had committed adharma, and, hence, he could not be defended. Vibhishana also seems to have made a distinction between the king and the country. An act of adharma by a king is an act of betrayal of his praja (people). The king then need not be defended. And, if he needs to be replaced, so be it, even if that calls for joining hands with the king’s enemies. Rama’s intent was to defeat Ravana and regain his wife, not to subdue Lanka. If so, could Vibhishana’s joining hands with Rama against Ravana be considered treason? Or, would dharma demand that Vibhishana stand with his king and kin even if the latter’s actions revolted against his ideals?

These are concerns that resonate in public affairs even in the modern age. When Adolf Hitler seized power in Germany, Thomas Mann left his homeland and even opted to broadcast against the fascist regime from the US and Britain during World War II. There were Indians, who campaigned against the Indira Gandhi government from the West during the Emergency. And every regime insists that the praja, or citizens, stand by its regressions from the founding ideals of the republic in the name of nationalism, and abuse those who refuse to comply in the name of dharma (constitutional ideals) as anti-nationals.

Returning to Vibhishana, little is known of his afterlife post the defeat of Ravana and his ascension to the throne of Lanka. Balamaniamma, one of the greats of Malayalam poetry, visits Vibhishana and finds him restless even on the throne. The vision she unveils through him in Vibhishanan (1964) is that dharma is no less an unkind ideal as adharma is. Vibhishana is hounded by the doubt that his dead ancestors would condemn him as the destroyer of their clan. He recalls his encounter with Ravana, when he asked him: “Drop the war cry, should those with evolved intellect be playing with human lives?” Thereafter, he is reminded of Sita’s agnipravesha and wonders if dharma can be as unkind as adharma. She finds echoes of Vibhishana’s bewilderment in modern times as dharma is invoked even in use of the atom bomb, and asks if wisdom has been defeated in time’s laboratory, as the heart had lost its battle in the days of Rama!

Dharma, it is often said, is the foundational principle of Indic civilisation. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata, foundational epics of India, certainly seem to think so, and both privilege it over fealty to blood and land. Vibhishana was one of the first persons to flag this vision. His motives for doing so should not persuade us to ignore the ethical dimension in his revolt.

This article first appeared in the print edition on October 27, 2019 under the title ‘Dharma and dilemma’.

Source: indianexpress

This post is for sharing knowledge only, no intention to violate any copy rights

Source: indianexpress

This post is for sharing knowledge only, no intention to violate any copy rights